INDIAN ARMED FORCES CHIEFS ON

OUR RELENTLESS AND FOCUSED PUBLISHING EFFORTS

SP Guide Publications puts forth a well compiled articulation of issues, pursuits and accomplishments of the Indian Army, over the years

I am confident that SP Guide Publications would continue to inform, inspire and influence.

My compliments to SP Guide Publications for informative and credible reportage on contemporary aerospace issues over the past six decades.

Self-reliance & Sustainability

The aerospace sector, military and civil, has bright prospects as the demand for air travel and military aircraft will only increase in the coming decades. The industry needs to be energised with a combination of new technologies, innovative policies and no riders.

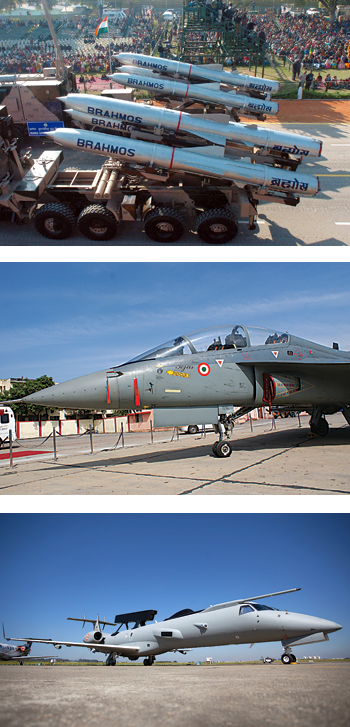

An advertisement by the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO) proclaims “Driving Self Reliance for Strength, Security and Peace”, while also boasting of how DRDO’s technologies and innovation have equipped the Indian armed forces with state-of-the-art weapon systems and technology solutions. What is glaringly missing in the advertisement is the word ‘indigenous’! DRDO and the other defence public sector undertakings (DPSUs) have several systems and weapon platforms being either developed or under production. In December 2013, amidst much fanfare, the Indian-built light combat aircraft (LCA) Tejas was granted initial operational clearance (IOC). A similar celebration was witnessed in late 2011 for a similar clearance, namely IOC, which is now being termed as an “interim clearance”.

The various systems under development by DRDO and the percentage of their indigenous content are as follows:

- Airborne early warning and control system – 33 per cent.

- BrahMos cruise missile (JV with Russia) – 35 per cent.

- Long-range surface-to-air missile (JV with Israel) – 40 per cent.

- Combat free-fall system – 65 per cent.

- Anti-tank missile – 70 per cent.

The LCA, 30 years in the making, has just about 60 per cent indigenous content, while the main battle tank (MBT) Arjun has about 55 per cent imported parts. The aim of the above elaborations was to give an insight of indigenous technology intensiveness.

The Indian Air Force

The Indian Air Force (IAF) has often been blamed for not encouraging or pursuing indigenisation and going in for big-ticket purchases from abroad. The inventory of the IAF is wide and varied in terms of technology and origin. The maintenance of weapons platforms ranging from vintage to state-of-the-art technology is a challenging task. Till date, anything and everything associated with aviation, more so military aviation, had the Hindustan Aeronautics Limited (HAL) stamp on it. The IAF has all along been its captive customer, buying whatever it produces, in whatever quantity or quality and at whatever cost and delays. Today, the IAF wants to break away from the stranglehold of HAL and its bureaucratic and political masters. It did not issue the request for proposal (RFP) for replacement of its Avro fleet. The spat between the two on this issue and that of the basic trainer aircraft is now public and needs no elaboration. While the IAF cannot encourage indigenisation to produce major weapons systems, it has always promoted small and medium enterprises (SME) to produce equipment for maintenance of the inventory.

The rationale behind extended use of equipment or weapon platforms has always been based on life review study reports initiated by the IAF with specialist advice rendered by DRDO, DPSUs and other scientific institutes. The effective utilisation of the inventory, if product support was not available, is made through the option of ‘reduce to produce’; the simplest of options but having an adverse effect on the strength of the inventory, yet with no other choice due to diminishing support from the foreign original equipment manufacturer (OEM).

The dire situation and inescapable necessity for the maintenance of the inventory has forced the IAF to search for a solution in indigenisation. The IAF has had, for long, maintained an organisation under its Maintenance Command (MC) which has a string of base repair depots (BRD), each assigned a specific role, which include repair and overhaul of fighter and transport aircraft, missiles, support vehicles, radars and a variety of other equipment. Stringent safety and operational standards through testing and certification by the concerned agencies as also by the concerned BRD is ensured. Vendors are informed in advance that the requirements of the IAF are maintenance requirements with no availability of technology transfer or even an original design. The vendors are encouraged to study the maintenance manuals, along with samples and use the expertise of the BRD.

Over the years, the IAF has found that the Indian aerospace industry in the private sector has the capability and desire of being the most technologically advanced. The IAF has simplified procedures to identify vendors within the ambit of the existing procurement procedures, but has not lowered the standards. The response from the industry had prompted the former Chief of the Air Staff, Air Chief Marshal N.A.K. Browne to state that the BRDs in collaboration with SMEs can produce modern combat aircraft.

Indigenisation in Defence

The list of failures and delays in the Indian defence sector is long. The secrecy in the activities of DRDO and DPSUs whether the questionable priorities or failed or delayed projects, do not deter the wise men who control such activities and know full well that misadventures and waste of public funds would never be publicly known.

Foreign direct investment (FDI) was heralded as the panacea for the ills plaguing the Indian defence industry. Can a solution to the woes be imported? Can producing defence equipment under licence be termed as indigenisation? Can transfer of technology (ToT) help the Indian defence industry acquire the most modern technology to become self-sufficient? These need answers.

FDI has remained a mirage on the horizons capped at 26 per cent with increase up to 49 per cent only on a case-by-case basis and restricted to high-end technology. It is unlikely that a foreign manufacturer would participate in a joint venture and transfer critical technology when its investment and control is restricted to 26 per cent with no assurance that the Indian armed forces would accept the product. This measure has often been justified as an essential security despite the private industry crying hoarse for increase. A genuine joint venture has to be a 50:50 agreement and 74:26.

The Indian aerospace industry and the bureaucracy have been conveniently stuck in the comfort zone of ToT, a clause included in almost every contract for the IAF. However, ToT only provides the latest in production techniques but no access to intellectual property of design and development. There is politics to play in this game too. Notwithstanding the ‘strategic partnership’ agreements with some countries, India continues to remain a mainly non-aligned nation. It is therefore unrealistic to expect unfettered cooperation in areas of sensitive high-end technology.

Another important issue that affects defence production is that of human resources. Currently, DPSUs do not feature on the list of dream jobs for most graduates from Caltech, MIT, Stanford or even the prime Indian institutes. The bureaucratic environment and the low prioritisation of R&D, as evidenced by paltry budget allocations (DRDO gets a little over five per cent of the total defence budget), have resulted in uninspiring opportunities for budding scientists. Barring a few Indian universities that have aviation or aerospace related subjects on their curriculum, the domestic pool of talent is miniscule. Shortage of qualified scientists and engineers, something that Dr Homi Bhabha had warned about when he put together the nuclear establishment in the late 1940s has come to haunt the Indian aerospace industry.

Way Ahead

India ranks among the top ten countries in the world in terms of military expenditure. The country’s defence budget has grown significantly in recent years. Considering that imports account for 70 per cent of the expenditure on defence procurements, offset obligations worth $21.4 billion will be generated at 30 per cent of the contract value. The largest contract yet to be signed for 126 medium multi-role combat aircraft (MMRCA) is estimated to be worth around $20 billion. The tender document places a 50 per cent offset liability on vendors. This offset business is expected to flow into India through Tier-I and Tier-II vendors of global OEMs. SMEs can expect to corner a substantial chunk of this business. While the Government of India (GoI) has been undertaking initiatives to encourage participation by the private sector, there is scope for more such initiatives.

Apex industry bodies such as the Confederation of Indian Industry (CII) and the Associated Chambers of Commerce and Industry (ASSOCHAM), have been calling for a review of the production policies, which as per their complaints are heavily lopsided in favour of the DPSUs. The policy on FDI has failed as total foreign investments in the defence sector in the last decade has been a meagre $5 million as against over $280 billion FDI received across different sectors, thus making a strong case for an increase in FDI. It has also been suggested that the GoI reviews the procedure proposed in DPP 2013 for calculating the value of indigenous content, as it being a complex process, discourages Indian vendors from participating in procurement programmes. There is also a need to sponsor R&D projects in the private industry with a provision for special tax incentives, either by GoI or through the IAF to encourage development of critically advanced technologies.

Apart from defence, as the Indian economy grows, there are opportunities in the civil and cargo aviation sectors too. Openings exist for maintenance and repair, avionics, communication systems, control system design, software design among others. Emerging economies like India, which provide significant cost benefits, are being increasingly considered as an outsourcing destination. The GoI must ensure that the private industry gets a level playing field.

Aerospace industry is a high technology and high-risk industry, which translates into high costs. There is the need to concentrate on high-end technologies, which can further uplift peripheral technologies. The Indian aerospace and defence industry needs rapid development of domain knowledge, which would require active industry-governmentacademia partnership with leading technology institutes across the globe, to upgrade, design and offer tailor-made courses for the aerospace and defence industry in India. The aerospace sector also has tremendous scope for supporting various other industries and thus can be a significant contributor to the economic growth.

It is time the DPSUs (read HAL) shed their holier than thou attitude and take the path of joint ventures and public-private partnerships (PPP). The GoI should encourage this path and not place obstacles with riders such as, “within the government approved framework”. While India boasts of the largest aerospace industry in Asia, it has no vision or strategy. The management and organisation of the entire aerospace industry, civil and defence, needs a facelift. A National Aerospace Policy that caters to the interests of all stakeholders, duly synchronised where necessary, is the immediate requirement, along with setting up of an Aeronautics Commission and a dedicated Department of Aerospace with other supporting organisations.

Encourage Indigenisation

The rapid pace of obsolescence has made it difficult for even private firms to keep up with the equally rapid pace in advancement of technology. One agrees that as indigenous capability develops, the products initially may not be internationally competitive, but a fledgling indigenous industry needs the support of a ready and sizeable market until past the learning curve.

The aerospace sector, military and civil, has bright prospects as the demand for air travel and military aircraft will only increase in the coming decades. The industry needs to be energised with a combination of new technologies, innovative policies and no riders. Ideological mindset on defence and security issues has to change. Some changes have been introduced while some others are in the pipeline. These should be followed without fear of failure or else the nation will be doomed to a lifetime of dependence on imports.