INDIAN ARMED FORCES CHIEFS ON

OUR RELENTLESS AND FOCUSED PUBLISHING EFFORTS

SP Guide Publications puts forth a well compiled articulation of issues, pursuits and accomplishments of the Indian Army, over the years

I am confident that SP Guide Publications would continue to inform, inspire and influence.

My compliments to SP Guide Publications for informative and credible reportage on contemporary aerospace issues over the past six decades.

Operational Status of the IAF

Considering the destructive potential of modern weapons, shortfalls in capability could well result in the destruction of the state itself, making evaluation of the performance of its military an academic exercise

Stripped of jargon, the operational status of an organisation is the extent of its ability to accomplish tasks which are likely to be assigned to it. It is essential that likely tasks are visualised and assessed as accurately as possible.

Assessment of Capabilities and Performance

For commercial entities, return on investment is the primary concern. In the area of development, the aim would be to provide cost-effective facilities, transportation, utilities, etc, to an area or population base and then to maintain or even expand these. Evaluation of the capabilities of such organisations can be assessed from balance sheets, created infrastructure on the ground and the improvement in quality of life of the intended beneficiaries after the task is completed.

Certain areas such as health care, fire and accident relief, disaster management and law and order, require organisations to monitor trends, act to deter adverse developments and also to visualise and prepare to deal with sudden and possibly unexpected emergencies. They have to be equipped, manned and trained for contingencies whose likelihood, duration, severity and many other factors cannot be accurately predicted.

The armed forces are foremost this category. A prime task is deterrence and success here can only be measured by maintenance of status quo or absence of armed conflict. Considering the destructive potential of modern weapons, any shortfalls in capability could well result in the destruction of the state itself, making evaluation of the performance of its military an academic exercise for historians. This makes operational status assessments of the armed forces vital and a high degree of accuracy of assessment becomes essential for national security.

Irrespective of the perceptions of some, the profession of arms is a complex one requiring skills and hands on experience. Assessment of the operational capabilities of the armed forces the world over is therefore done by people within the organisation and then reported to the political masters who carry the ultimate responsibility. The danger of this is that it becomes difficult to carry out an unbiased evaluation of one’s own capabilities. Organisations are often harsh with those who voice criticism. A ‘do not rock the boat’ syndrome comes into force. This is a universal problem.

Operational Status of the IAF in the Past

In its formative years during World War II, there was barely any time to recruit personnel, give them some form of training and send them off to war to learn on the job. In these circumstances, operational status assessment was based on actual combat performance. Post World War II till up to a decade ago, the Indian Air Force (IAF) had limited contact with other air forces and this isolation to some extent affected its operational philosophy and doctrine. The IAF appeared to prepare and train for the last war, a malaise common to most armed forces in the world.

Prior to 1962, a few senior offices with combat experience voiced concerns about the erosion of the capabilities of the IAF and the inability to provide a credible deterrent to the adversary across the North-eastern border. They were silenced and ignored. 1962 brought the nation into military conflict with a major Asian power and resulted in a trauma that exists even today. The nation learned the hard way that rhetoric and orders that are impossible to carry out coupled with commanders lacking competence, cannot achieve results. Resources, training, leadership and professional assessments of what is possible and what is not are needed. The nation was totally unprepared to fight a large force in the mountains and did not use the IAF in combat.

Between 1962 and 1965 there was a rapid expansion of the IAF. It is possible that some aspects of operational preparedness were compromised in the effort to build up force levels. 1965 showed up some deficiencies in inter-services coordination, tactics and some other aspects. Ironically this was in a force that had excelled in close support to ground forces in Burma two decades earlier. These lessons fortunately began to be absorbed and 1971 saw much better cooperation amongst the three services.

Operational preparedness of larger formations continued to be assessed by exercises which were not very realistic. Individual skills of flying units were invariably assessed by weapons delivery results in ideal conditions over familiar terrain with lots of safety restrictions in force. They were unrealistic and divorced from the realities of combat. The danger was that people were trained for exercise environments and not for conditions resembling combat. The IAF had limited night, electronic warfare, adverse weather and precision attack capabilities and a mindset appears to have come about of ignoring these aspects despite the fact that potential enemies were developing these capabilities. Simulators in military aviation were always a low priority area in the IAF of the past and sophisticated pure flying and mission simulators were not procured till recently. Weapons effect planning became a part of serious operational planning quite late and target-to-weapons matching was often done based on unrealistic gunnery meet results. However, the IAF did finally get a dedicated operational evaluation organisation.

The Present

A welcome change along with the force modernisation starting in the late 1980s has been the exposure of the IAF to the doctrine, tactics and equipment of other modern air forces during various exercises in the last ten years. This has boosted confidence, given valuable lessons and showed up weak areas. Barring some juvenile remarks by odd individuals, the majority of participants have greatly enhanced their professional skills and benefited from the exposure during these exercises.

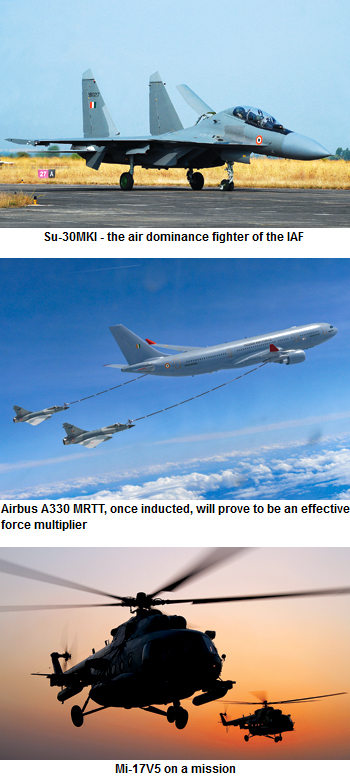

Acquisition of long-range strike capabilities through inflight refuelling capability, induction of airborne command and control systems, integrated electronic warfare equipment, standoff precision guided weapons, secure real time communications with data links, night and adverse weather capability and real time accurate target intelligence are some of the aspects which have improved the operational capability of the IAF. It is hoped that these assets are gainfully exploited by our commanders to prepare for the next war and not to fight the last one again.

Simulation has finally been accepted by the service for activities ranging from basic pure flying to mission profile training and validation as well as for plans validation. As weapons become more expensive, firing them off on weapons ranges to give operators the feel of using them is something no force can afford. Precision weapons have almost standardised weapons accuracies for a particular platform so that weapons effect planning is much more realistic.

The Way Forward

These trends along with increased use of unmanned systems, cyber warfare and stealth will dominate air wars in the future. The operational status of the IAF will have to be assessed in such realistic scenarios mainly through simulation. This will also help in eliminating bias in assessment. Commanders must still have the courage to project true force capabilities to their political masters and not tell them only what they want to hear.

The IAF is faced with a drawdown of flying assets and this downwards slide will continue well past the mid-2020s. The need is to make a realistic assessment of what it can achieve with such depleted force levels. Tasks have to be matched to capabilities as otherwise tasks will remain as unachievable dreams.

One of the parameters that define readiness is availability of forces. Aircraft serviceability of the prime and the most numerous fighter asset of the IAF, the Su-30MKI, is hovering around the 50 per cent mark as per open source reports. This is an alarming figure for the IAF where 75 per cent had been the minimum acceptable level. This combined with the drawdown caused by withdrawal of obsolete assets, renders the situation alarming. The IAF will soon be unable to pose a credible deterrent. Low serviceability is one deficiency that can and has to be corrected in house. If the malaise of low serviceability is not rectified, talking about a two-front conflict with containment on one front and large-scale offensive action on the other, will remain as mere rhetoric.

The last factor is a change in mindset. Senior commanders must at least listen to new concepts instead of discarding them because they were formulated by juniors. Age is not the only measure of wisdom. All stakeholders must realise that if war is too important a business to be left to the generals, national security is too important a business to be left solely to the political leadership and the bureaucracy.