INDIAN ARMED FORCES CHIEFS ON

OUR RELENTLESS AND FOCUSED PUBLISHING EFFORTS

SP Guide Publications puts forth a well compiled articulation of issues, pursuits and accomplishments of the Indian Army, over the years

I am confident that SP Guide Publications would continue to inform, inspire and influence.

My compliments to SP Guide Publications for informative and credible reportage on contemporary aerospace issues over the past six decades.

5th-Gen Options

The Indian Air Force (IAF) was quick to recognise the immense potential of fifth-generation fighters and around five years ago, seemed set to induct not one, but two types

When the Lockheed Martin F-22 Raptor, a fifth-generation, twin-engine, stealth fighter aircraft was introduced by the United States Air Force (USAF) in December 2005, it created a stir. Analysts opined that if an attacking aircraft could be rendered “invisible” to the enemy defences on account of its low-observable characteristics, it would enjoy immense advantage. Conversely, the foe would find it well-nigh impossible to engage an intruder he could not “see”. As America’s potential adversaries stepped up efforts to develop their own fifth-generation fighters, its allies demanded these “invincible” platforms for their own air forces.

The mystique surrounding fifth-generation fighters abated a little when the F-22 programme was terminated on account of high costs after only 195 jets were built. But its successor, the Lockheed Martin F-35 Lightning II, has fared better. This singleengine stealth multirole fighter is projected to become the largest and most expensive weapon system in history, based on its forecast production of over 3,000 jets and its estimated lifetime cost of $1.5 trillion.

The Indian Air Force (IAF) was quick to recognise the immense potential of fifth-generation fighters and around five years ago, seemed set to induct not one but two types – the Sukhoi/Hindustan Aeronautics Limited (HAL) Fifth Generation Fighter Aircraft (FGFA) and the indigenous Advanced Medium Combat Aircraft (AMCA). However, recently, the FGFA project has collapsed, the AMCA is still a distant dream and the IAF cannot realistically hope to acquire the F-35. Besides, the shortage of conventional combat squadrons in the IAF has turned acute. It is staring at an imminent drop below 30 squadrons against the authorised strength of 42 squadrons (each consisting of 18 jets), the assessed minimum necessary to tackle a two-front collusive threat from Pakistan and China. In such circumstances, a hugely expensive stealth fighter seems like an avoidable extravagance. So does the IAF really need a fifth-generation fighter aircraft? The short answer is: Yes it does, but perhaps not just yet.

FOCUS ON THE FIFTH GENERATION

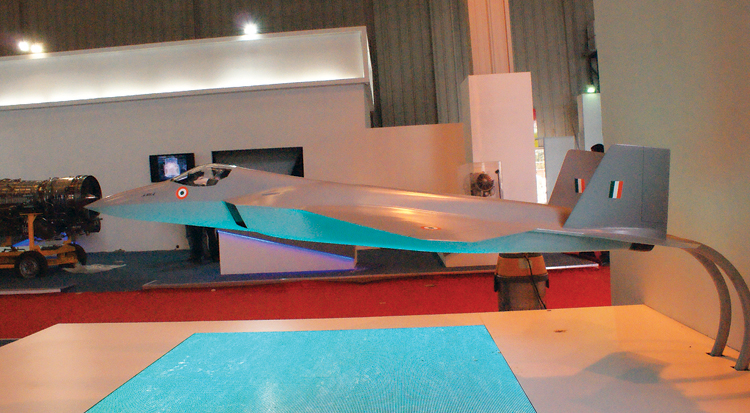

It was in 2007 that India and Russia began exploring the possibility of jointly producing a fifth-generation combat aircraft for the IAF. In 2010, the two countries signed a $295 million design contract for the co-development of the Sukhoi/HAL Perspective Multi-role Fighter (PMF) or FGFA based on the Su-57 prototype, the T-50. The projected production run was as high as 250 jets for Russia and 144 for India by 2022 at a cost of around $30 billion. Meanwhile, in 2008, India’s Aeronautical Development Agency (ADA) also got into the act with a preliminary study on an indigenous stealth multirole jet to be known as the AMCA. Design work on this fifth-generation fighter commenced in 2010.

The PLAAF intends to induct a large number of fifthgeneration fighters and the Pakistan Air Force (PAF) is likely to get some of these platforms too

Strangely enough, there are no clearly defined attributes of a fifth-generation fighter aircraft. It appears it is simply one that incorporates all proven features of fourth-generation designs, besides some new characteristics such as comprehensive all-aspect stealth, low probability of intercept radar (LPIR), high-performance airframe, high-performance engine capable of supersonic cruise without afterburner or super-cruise, advanced avionics with long-range sensors, and networked data fusion to provide full battle-space situational awareness. The armament must be carried internally to keep the aircraft’s radar cross-section (RCS) low.

INDIA’S IMPERATIVES

The F-22 Raptor was the world’s only operational stealth fighter for almost a decade before a variant of the F-35 achieved initial operational capability (IOC) in July 2015. More recently, China’s Chengdu J-20A entered operational service in September 2017 with the People’s Liberation Army Air Force (PLAAF). It will be followed by China’s Shenyang J-31 which may attain IOC by 2020. Russia for its part, claims that its Su-57 will be operational in 2019. However, the Russian Air Force (RAF) has only ordered a dozen such jets indicating a dismal lack of faith in its capabilities.

As per reports, the PLAAF intends to induct a large number of fifth-generation fighters and the Pakistan Air Force (PAF) is likely to get some of these platforms too in not too distant a future. In fact, heartened by their successful cooperation on the JF-17 lightweight fighter, Pakistan is even considering building a fifth-generation jet with Chinese assistance. The only way for the IAF to keep abreast of its potential adversaries and penetrate their fearsome air defences with low chances of detection and interception, would be to have its own fleet of fifth-generation combat aircraft. It would also need to develop effective countermeasures against intruding enemy stealth jets.

THE FGFA GRIDLOCK

Building fifth-generation fighters from scratch is a terribly difficult and costly proposition and very few attempts across the world have succeeded. That is why development of the FGFA seemed such an excellent idea. However, following detailed evaluation of the T-50 prototype, the IAF found serious shortcomings in the plane’s stealth engineering, engine, radar which had limited coverage and capability and weapon-carrying capacity. The sought more than 40 changes in it platform. Disagreements also increased about work share, transfer of technology (ToT) and costs. HAL however strongly backed the project, claiming that the experience gained would ultimately help in the AMCA project. The IAF, hamstrung by severe lack of resources and budgetary support, finally decided that fifth-generation fighters can wait. It first needs to acquire fighters in large numbers at affordable cost. Earlier this year, India asked Russia to proceed alone with developing their fifth-generation fighter. India however left the option open to join the project later or buy some Su-57 jets off-the-shelf if necessary.

For some time, rumours abounded that the IAF might make a bid for the Lockheed Martin F-35A. However, the IAF quickly scotched such speculation. Apart from the uncertainty about the US government clearing the sale of such an advanced fighter jet to India, the F-35A makes little sense. Lockheed Martin would neither agree to produce the fighters in India nor to transfer technology. US military aircraft also come with strings attached. For instance, after holding out for years, India on September 6, 2018, signed the enabling agreement COMCASA without which it failed to obtain specialised equipment for encrypted communications for its US-built aircraft such as the Boeing C-17 Globemaster III, the Lockheed Martin C-130J Super Hercules and the Boeing P-8I Poseidon.

THE AMCA: ADVANTAGE OR MIRAGE?

The IAF also realises that with the government reluctant to sign on the dotted line for fighter jet imports, there is no alternative to indigenous aircraft. That is why, despite reservations over their numerous shortcomings, it plans to induct at least 18 squadrons of the HAL-made Light Combat Aircraft (LCA) Tejas fighters by 2032. The Tejas Mk-2 would probably replace the existing MiG-29s, Jaguars, and Mirage 2000s and become the mainstay of the IAF by numbers. An indigenous fifth-generation fighter such as the AMCA would complete the picture and may also act as a force multiplier to compensate for some of the IAF’s missing squadrons. The IAF is backing the AMCA programme wholeheartedly since it seems to be the only hope of getting a fifth-generation fighter.

However, the Tejas experience where it took decades to develop a single-engine fighter is not a good augury. The AMCA being a twin-engine, stealth, super-manoeuvrable and super-cruise aircraft, is perhaps an order of magnitude more challenging. Much effort and plenty of luck will be needed to successfully develop crucial fifth-generation technologies. Speedy timelines and realistic goals need to be set to ensure that the project progresses as planned.

As India strives to develop a fifth-generation fighter, it would be unwise to ignore the emerging sixth generation

The main challenge is developing an engine with the required performance including thrust vectoring and super-cruise. In theory, the AMCA will be powered by a domestically manufactured Kaveri K9 or K10 engine, currently under development by the Gas Turbine Research Establishment (GTRE). Only after the Kaveri is ready, hopefully by 2019, can serious work on the airframe begin. As Plan B, the AMCA may initially fly with two General Electric F414 turbofans and get indigenous engines later. Other major challenges include the AESA radar and the development of radar absorbing materials (RAM). The ADA has perhaps wisely decided to concentrate on geometric stealth – that is, shaping the aircraft for minimum RCS from various angles rather than material stealth, which would need the development of RAM to reduce the RCS. Even so, the AMCA’s first flight is not expected before 2032.

THINKING AHEAD

Given that it could take up to two decades for the IAF to get the AMCA in operational service, it realises the need to put in place robust defences against Chinese and possibly Pakistani fifth-generation fighters. The IAF claims that the Su-30MKI radar can detect Chinese fifth-generation fighters. If this is true, it would bear out Western scepticism about the quality of Chinese stealth design. It would also mean the IAF may have at least 10 to 15 years to replenish its dwindling fleet of fourthgeneration fighters before the PLAAF’s fifth-generation fighters begin to constitute a significant threat.

India is also close to signing an agreement to acquire the Russian S-400 Triumf air defence missile system. The S-400’s highband targeting radar can engage a stealth jet at short range. The S-500, due to be deployed by Russia in 2020, may even be advanced enough to generate a weapons-quality track on an F-22 or F-35 stealth fighter.

As India strives to develop a fifth-generation fighter, it would be unwise to ignore the emerging sixth generation. A sixth-generation fighter, likely to be first fielded by the US after 2030, is expected to be an aircraft with all the characteristics of fifth-generation jets plus directed-energy weapons and/or hypersonics. Some analysts believe that advanced sensor technology will render stealth design fruitless, while fighter agility, electronic warfare and infrared obscuring devices will correspondingly gain in importance. Countries such as France, Germany and the United Kingdom appear to have given up attempts to build pure fifth-generation jets and instead propose to directly start work on the sixth generation platform. The IAF and the AMCA design team would do well to keep this in mind.