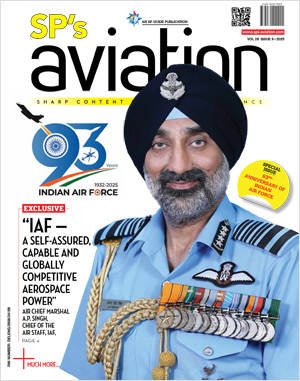

INDIAN ARMED FORCES CHIEFS ON OUR RELENTLESS AND FOCUSED PUBLISHING EFFORTS

The insightful articles, inspiring narrations and analytical perspectives presented by the Editorial Team, establish an alluring connect with the reader. My compliments and best wishes to SP Guide Publications.

"Over the past 60 years, the growth of SP Guide Publications has mirrored the rising stature of Indian Navy. Its well-researched and informative magazines on Defence and Aerospace sector have served to shape an educated opinion of our military personnel, policy makers and the public alike. I wish SP's Publication team continued success, fair winds and following seas in all future endeavour!"

Since, its inception in 1964, SP Guide Publications has consistently demonstrated commitment to high-quality journalism in the aerospace and defence sectors, earning a well-deserved reputation as Asia's largest media house in this domain. I wish SP Guide Publications continued success in its pursuit of excellence.

- A leap in Indian aviation: Prime Minister Modi inaugurates Safran's Global MRO Hub in Hyderabad, Calls It a Milestone

- All about HAMMER Smart Precision Guided Weapon in India — “BEL-Safran Collaboration”

- India, Germany deepen defence ties as High Defence Committee charts ambitious plan

- True strategic autonomy will come only when our code is as indigenous as our hardware: Rajnath Singh

- EXCLUSIVE: Manish Kumar Jha speaks with Air Marshal Ashutosh Dixit, Chief of Integrated Defence Staff (CISC) at Headquarters, Integrated Defence Staff (IDS)

- Experts Speak: G20 Summit: A Sign of Global Fracture

Humanitarian Crises Boil Over

There are many voices that remain unheard in the current humanitarian crisis sweeping the globe

|

The Author is former Chief of Staff of a frontline Corps in the North East and a former helicopter pilot. He earlier headed the China & neighbourhood desk at the Defence Intelligence Agency. He retired in July 2020 and held the appointment of Addl DG Information Systems at Army HQ. |

The desperate scenes of death and destruction due to the relentless bombing of Gaza blaring out of all television channels may be mistaken as the only humanitarian crisis that needs global attention and empathy. No doubt the death of over 9,000 in Gaza in the past roughly one month, since the October 7, 2023 terrorist attack by Hamas in South Israel that killed over 1,400 Israeli civilians including women and children triggered a bloody response from Israel, must be recognised as a huge crisis situation. Almost half of the total 2.3 million population is displaced and surviving under dire straits as Gaza is bombed out daily. But it would be a mistake to ignore even more profound and catastrophic situations already existing and others that are getting aggravated as time passes.

The UNHCR reported a staggering 108.4 million forcibly displaced individuals by the end of 2022, with a shocking 43 million being children under 18 years old.

As a Chief Humanitarian Officer of the UN Mission in Lebanon some two decades back, I had to receive 45 Kurdish refugees from Israel who had crossed over from Syria and organise their housing in UN containers and provide for their food clothing and initiate documentation through the UNHCR. Later it was revealed that in 2006, when the Lebanon-Israel border flared up again, they were moved further North to another container camp but there is no closure to the issue. This is typical of what confronts the millions displaced every year due to wars, terrorism, despotic regimes, ethnic cleansing or sometimes due to famine, floods and fire as well.

Where are these refugees headed and hosted? What is their future, especially the huge number of children? Will they be able to assimilate into societies hosting them like the Europe where millions fled in 2015/16? Is the comity of nations doing enough to stem the tide and care for those already displaced? Are some countries and human trafficking syndicates exploiting the refugees for their narrow ends? These and many more questions pop up as anti-migrant sentiments grow in Europe and elsewhere. Migrants have become a hot potato theme in electoral battles and seen the rise of the far-right. Many governments in Europe have been overthrown precisely on the migrant issue.

Turkey currently hosts over 3.6 million refugees, predominantly Syrians who fled due to persecution after the failed attempts to overthrow the Assad regime in 2011.

The UNHCR put the figure at 108.4 million who were forcibly displaced at the end of 2022. Out of this, a staggering 43 million are children below 18 years of age. These figures dwarf the current crisis engulfing Gaza strip with a total population of just over 2.3 million. Nearly 50 per cent of the refugees came from just three countries, Syria, Ukraine and Afghanistan. As of May 2023, more than 110 million individuals were forcibly displaced worldwide. This marks the largest ever single-year increase in forced displacement in UNHCR's history.

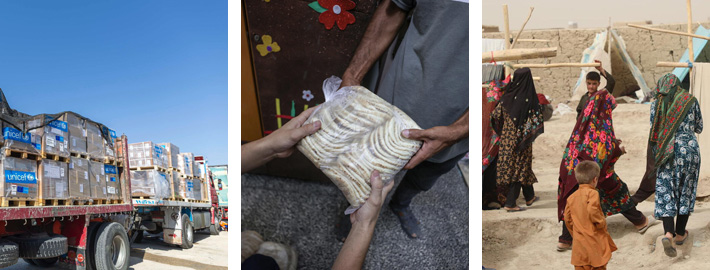

Turkey hosts the most refugees, pegged at over 3.6 million, mostly Syrians forced to flee due to prosecution after the failed attempts to overthrow the Assad regime in 2011. More than 8.2 million Afghans had been driven out of their homes and their country into neighbouring countries by conflict, violence and poverty. Pakistan hosts an estimated 4 million Afghans out of which over 1.6 million are undocumented. The Pakistani caretaker government had asked the undocumented refugees to leave the country by November 1, 2023 and has since moved in to tear down shanties and conduct raids on Afghan settlements. Tens of thousands have since fled back into Afghanistan unwillingly where they fear for their lives under the Taliban. But what choices do they have?

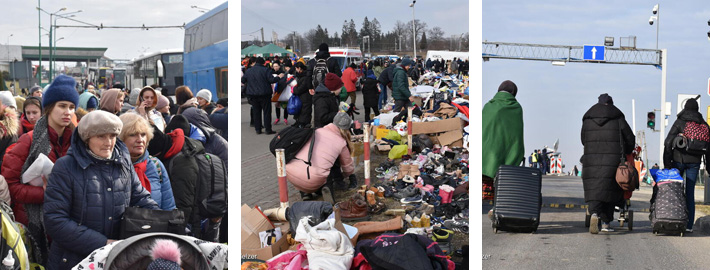

The war in Ukraine has pushed more than eight million people to flee the country, triggering Europe's largest refugee crisis since World War II. More than five million are internally displaced. That accounts for roughly a third of its pre-war population of 41 million. To put it in perspective, the European continent saw some one million refugees during the 2015/16 wave from Africa and the Middle East, and up to four million refugees during the Balkan crisis when Yugoslavia imploded in the 1990s. Hence the current influx is punishing when compared with previous numbers.

Russia has taken in about 2.9 million mainly Russian speaking people, or 35 per cent of Ukrainian refugees in Europe. Neighbouring Poland, already home to an estimated 1.3 million Ukrainians, has welcomed another 1.6 million. Poland along with Hungary and Czech Republic had earlier refused to accept any refugees from Africa and the Middle East arguing that the non-EU migrants could pose a security threat. While it can be argued that all migrants cannot be categorised as security threat because of the actions of some, the fact remains that eight years since the wave entered Europe, there have been large-scale violence, riots, knife attacks and arson in many European cities but no such incidents in Poland, somewhat proving their point. The pro-Palestine rallies spearheaded by these very migrants who were earlier welcomed into many European cities has further sharpened divisions with many on the Right calling for their deportation to countries of origin.

As the war continues, humanitarian needs are multiplying and spreading. An estimated 17.6 million people in Ukraine will need humanitarian assistance in 2023.

The UK is toying with the idea of sending asylum seekers arriving in the UK to a third country like Rwanda having paid the Rwandan government £140m for the scheme but it is entangled in a legal battle on fears for the safety of these migrants in Rwanda. Italy under far-right Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni has promised to crack down on hundreds of thousands of migrants crossing interminably in rickety boats across the Mediterranean.

Spurred on by worsening economic and political crises across Latin America, about 2.2 million people have already been apprehended at the US-Mexico border through August this year, compared to 2.38 million border encounters for all of last year. Naturally, the debate in the US 2024 electoral cycle is on how to stem the tide as mainly Democratic cities like New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, Houston and Denver are overwhelmed with refugees. This is as grim a situation as in Gaza strip with its total 2.3 million population. Yemen's already dire hunger crisis is teetering on the edge of outright catastrophe, with 17.4 million people now in need of food assistance and this has nothing to do with Israel.

In the days to come, as the 2024 general elections approach in India, migrants' issue will again capture centre stage as the fate of Palestinians will be ingenuously clubbed with those of illegal Rohingyas and Kukis and flogged by political parties to consolidate their vote banks. There will be little appetite to discuss how best to handle a humanitarian crisis and what can stabilise the situation in the regions from where these migrants flee to escape life-threatening situations.