INDIAN ARMED FORCES CHIEFS ON OUR RELENTLESS AND FOCUSED PUBLISHING EFFORTS

SP Guide Publications puts forth a well compiled articulation of issues, pursuits and accomplishments of the Indian Army, over the years

"Over the past 60 years, the growth of SP Guide Publications has mirrored the rising stature of Indian Navy. Its well-researched and informative magazines on Defence and Aerospace sector have served to shape an educated opinion of our military personnel, policy makers and the public alike. I wish SP's Publication team continued success, fair winds and following seas in all future endeavour!"

Since, its inception in 1964, SP Guide Publications has consistently demonstrated commitment to high-quality journalism in the aerospace and defence sectors, earning a well-deserved reputation as Asia's largest media house in this domain. I wish SP Guide Publications continued success in its pursuit of excellence.

Contemporary & Upcoming

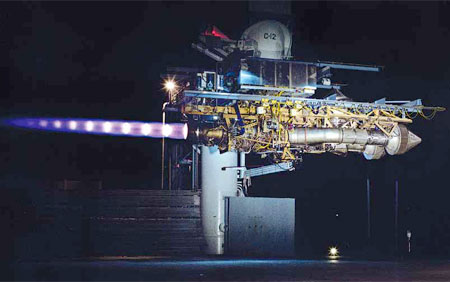

Design and development of military aero engines, especially jet engines, is a highly technologically complex task. Hence only a handful of manufacturers have been able to achieve global standards and stature.

The Merlin piston-engine powered Hawker Hurricanes and Supermarine Spitfires of the Royal Air Force (RAF) did indeed save the day for the UK by winning the Battle of Britain. But the world famous air campaign also exposed the limitations of piston-engines in powering the fighter platforms, the need of the hour being to beat the enemy with superior speed and height advantage. In their quest to fly higher and faster, designers of fighter aircraft hit a dead end with the propeller-driven, piston-engine aircraft whose speed could not be increased beyond a certain limit. The limit was essentially one of propeller efficiency. This seemed to peak as blade tips approached the speed of sound. It was realised that if the engine and thus the aircraft performance were ever to increase beyond such a barrier, a way would have to be found to radically improve the design of the piston engine, or a wholly new type of power plant would have to be developed. This was the motivation behind the development of the gas turbine engine, commonly called a ‘jet’ engine, which as the events unfolded, would usher in a revolution in aviation almost as spectacular as the Wright brothers’ first flight.

Post-World War II, while piston engines continued to power civil airliners for many years, in the field of military aviation they were rapidly displaced by the gas turbine. Fighters and bombers switched to the turbo jet, military transports and maritime-patrol aircraft used turboprops, and helicopters found it highly advantageous in changing over to turboshafts—all of them variations of the basic ‘jet’ engine. The change meant more power for less engine weight, far greater reliability, little cooling problems and safer kerosene-type fuels. By the 1950s, the use of jet engine, in one form or the other, became almost universal except for some specific types of cargo, liaison and special duty aircraft which sported piston engines as their respective power plants. By the 1960s, even the civil airliner changed over to jet engines. But it was not till a decade later when with the advent of high bypass jet engines, fuel efficiency matched or exceeded that of the piston-engine driven propeller aircraft, heralding the era of fast, safe and high-capacity economical travel for the general public.

The Evolution

From the earliest mere 4 to 5-kN thrust centrifugal-flow engines to the present-day up to 200-kN or more thrust axial-flow turbofans, with afterburning and variablethrust, sporting multi-stage compressors and turbines, and powerful enough to enable ‘super-cruise’ or supersonic speeds in dry power, it has been indeed a highly challenging and interesting journey in the evolution of jet engines.

To redux, eruption of Cold War between the two power blocs—Western & Eastern—resulted in an unprecedented arms race, which also gave catalytic push to ever faster fighters and bombers. The jet engines also went through metamorphic changes in complexities and capabilities. More and more powerful turbojets were introduced to expand the speed and altitude envelopes. The Super Sabre, first of the 100 series US fighters was also the first US fighter capable of supersonic flight in level flight. By this time, augmented thrust technique had been invented through the use of afterburners. Soon ‘Mach 2’ fighters were vying for superiority on both sides of the Atlantic. The English Electric Lightning was perhaps the only aircraft in the world to have ‘one on top of the other’ twin engine configuration with its Avon 301R afterburning engines. The other notable Mach 2 fighters of the era were the US F-104 Starfighter and the famous Mikoyan design of the Soviet bloc—the MiG-2—which earned the sobriquet of the most mass-produced jet fighter in the world with more than 10,000 variants taking to the skies.

Among the early jet engine designs there is one particular engine which stands out as a pièce de résistance or an engine extraordinaire—the Pratt & Whitney J58-P4, fitted on the 1960s US skunk-work design SR-71 Blackbird Mach 3 strategic reconnaissance aircraft. The J58-P4s were the only military engines designed at the time which could operate continuously on afterburner, and actually became more efficient as the aircraft went faster. Each J58 could produce 145-kN of static thrust. The J58 was unique in that it was a hybrid jet engine. It could operate as a regular turbojet at low speeds, but at high speeds it became a ramjet.

At lower speeds, the turbojet provided most of the compression and most of the energy from fuel combustion. At higher speeds, the turbojet throttled back and just sat in the middle of the engine as air bypassed around it, having been compressed by the shock cones and only burning fuel in the afterburner. At around Mach 3, the increased heating from the shock cone compression, plus the heating from the compressor fans, was already enough to get the core air to high temperatures, and hardly any fuel could be added in the combustion chamber without the turbine blades melting. This meant that the whole compressor—turbine setup in the core of the engine provided hardly any power, and the Blackbird flew predominantly on air bypassed straight to the afterburners, forming a powerful ramjet effect. No other aircraft did this including the competing Soviet aircraft, the famous MiG-25 Foxbat. The so-called tri-sonic aircraft, MiG-25 was built around its two massive Tumansky R 15(B) turbojet engines. Although the available thrust was sufficient to reach M 3.2, the engine design not having the same features as the Blackbird’s J58s, a limit of M 2.8 had to be imposed on the aircraft to prevent supposed total destruction of the engines due to overheating of the turbine blades.