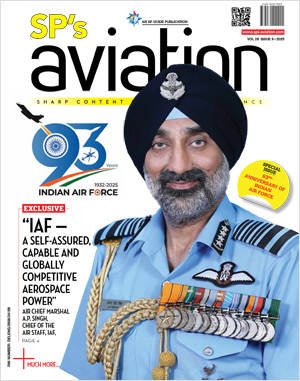

INDIAN ARMED FORCES CHIEFS ON OUR RELENTLESS AND FOCUSED PUBLISHING EFFORTS

The insightful articles, inspiring narrations and analytical perspectives presented by the Editorial Team, establish an alluring connect with the reader. My compliments and best wishes to SP Guide Publications.

"Over the past 60 years, the growth of SP Guide Publications has mirrored the rising stature of Indian Navy. Its well-researched and informative magazines on Defence and Aerospace sector have served to shape an educated opinion of our military personnel, policy makers and the public alike. I wish SP's Publication team continued success, fair winds and following seas in all future endeavour!"

Since, its inception in 1964, SP Guide Publications has consistently demonstrated commitment to high-quality journalism in the aerospace and defence sectors, earning a well-deserved reputation as Asia's largest media house in this domain. I wish SP Guide Publications continued success in its pursuit of excellence.

- A leap in Indian aviation: Prime Minister Modi inaugurates Safran's Global MRO Hub in Hyderabad, Calls It a Milestone

- All about HAMMER Smart Precision Guided Weapon in India — “BEL-Safran Collaboration”

- India, Germany deepen defence ties as High Defence Committee charts ambitious plan

- True strategic autonomy will come only when our code is as indigenous as our hardware: Rajnath Singh

- EXCLUSIVE: Manish Kumar Jha speaks with Air Marshal Ashutosh Dixit, Chief of Integrated Defence Staff (CISC) at Headquarters, Integrated Defence Staff (IDS)

- Experts Speak: G20 Summit: A Sign of Global Fracture

Eugene B. Ely (1886 – 1911)

On November 14, 1910 Eugene Ely took off from a temporary platform erected on the deck of the USS Birmingham. The wheels of the plane actually hit the sea before it attained enough speed to climb away. Eugene made it safely to shore—a distance of about 2 1/2 miles. The feat not only demonstrated the practicality of aviation at sea, but catapulted Ely to the front pages of virtually every newspaper in America.

Would any prudent Pilot choose to take off and land from an airstrip racing across the ocean at 30 knots? Not likely. That naval pilots—admittedly prone to execute incredible manoeuvres—have made it a routine procedure on aircraft carriers the world over is largely creditable to Eugene Ely, the first pilot ever to take off and land an aircraft aboard ship.

Eugene Burton Ely was born in Iowa on October 21, 1886. At 18, he began to take a passionate interest in automobiles, and their engines, quickly becoming one of America’s first racing drivers. In 1910, when a friend bought a biplane and didn’t know how to fly it, Eugene volunteered to try. He probably thought that flying should not be too difficult for a racing driver. Of course, he returned to earth with a tremendous bump. Feeling remorseful about the crash he bought the wreckage and proceeded to painstakingly repair it till it was airworthy again. This time he approached the task with greater caution, making the briefest of straight-line hops just to get the feel of the machine. Despite the initial mishap he took to flying naturally. Within weeks he had taught himself to fly and was awarded a certificate by the Aero Club of America. The next few months were intensely active, touring the entire country and giving flying demonstrations.

In the years following the Wright Brothers’ conquest of the air in 1903, pressure intensified on the US Navy to evaluate the new machines and their significance for naval operations. Glenn Curtiss was probably the person responsible for persuading the navy to act. He prophesied: The battles of the future will be fought in the air. The aeroplane will decide the destiny of nations... Encumbered as (big ships) are within their turrets and military masts, they cannot launch air fighters, and without these to defend them, they would be blown apart in case of war. Captain Washington Chambers, who worked for the Secretary of the US Navy, was convinced and roped in Eugene Ely for a demonstration.

On November 14, 1910 Eugene Ely took off from a temporary platform erected on the deck of the USS Birmingham. The wheels of the plane actually hit the sea before it attained enough speed to climb away. Eugene made it safely to shore—a distance of about 2 1/2 miles. The feat not only demonstrated the practicality of aviation at sea, but catapulted Ely to the front pages of virtually every newspaper in America.

Taking off from a ship was, no doubt, a remarkable feat. But could a plane land on a ship? Eugene Ely believed it could. This time the cruiser Pennsylvania was chosen. Its deck was modified with the first ever tail-hook system to safely grab the aircraft during its landing run. On January 18, 1911 Eugene, in a Curtiss pusher biplane specially equipped with arresting hooks on its axle, took off from Selfridge Field and headed for the San Francisco Bay. Sighting the Pennsylvania, he headed straight for the ship, cutting his engine when he was only 75 feet from the fantail, and allowed the plane to glide onto the deck, touching down at a speed of 40 mph. As the biplane raced along, the hooks on the undercarriage caught the ropes stretched between large bags of sand that had been placed along the entire length of the runway, exactly as planned. The forward momentum of the aircraft was quickly retarded and it was safely brought to a complete stop. The cruiser’s Captain Charles F. Pond called it the most important landing of a bird since the dove flew back to Noah’s ark. He later reported, Nothing damaged, and not a bolt or brace startled, and Ely the coolest man on board. Eugene Ely was greeted with a barrage of cheers, boat horns and whistles. There is no doubt that his daring flight that day, during the early history of aviation, was one of the most outstanding achievements made by any of the pioneer aviators.