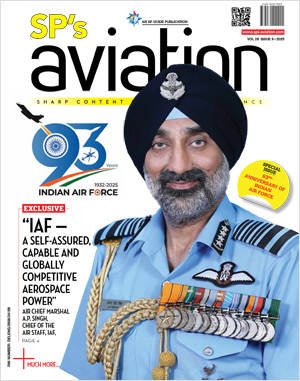

INDIAN ARMED FORCES CHIEFS ON OUR RELENTLESS AND FOCUSED PUBLISHING EFFORTS

The insightful articles, inspiring narrations and analytical perspectives presented by the Editorial Team, establish an alluring connect with the reader. My compliments and best wishes to SP Guide Publications.

"Over the past 60 years, the growth of SP Guide Publications has mirrored the rising stature of Indian Navy. Its well-researched and informative magazines on Defence and Aerospace sector have served to shape an educated opinion of our military personnel, policy makers and the public alike. I wish SP's Publication team continued success, fair winds and following seas in all future endeavour!"

Since, its inception in 1964, SP Guide Publications has consistently demonstrated commitment to high-quality journalism in the aerospace and defence sectors, earning a well-deserved reputation as Asia's largest media house in this domain. I wish SP Guide Publications continued success in its pursuit of excellence.

- A leap in Indian aviation: Prime Minister Modi inaugurates Safran's Global MRO Hub in Hyderabad, Calls It a Milestone

- All about HAMMER Smart Precision Guided Weapon in India — “BEL-Safran Collaboration”

- India, Germany deepen defence ties as High Defence Committee charts ambitious plan

- True strategic autonomy will come only when our code is as indigenous as our hardware: Rajnath Singh

- EXCLUSIVE: Manish Kumar Jha speaks with Air Marshal Ashutosh Dixit, Chief of Integrated Defence Staff (CISC) at Headquarters, Integrated Defence Staff (IDS)

- Experts Speak: G20 Summit: A Sign of Global Fracture

FBO - The Dire Need

General aviation operators tend to be small in size—some of them operating a single or maybe two aircraft. It is not possible for them to have facilities at any place except their own base and hence the need for FBOs. However, the current volume of general aviation traffic is not adequate for a large number of FBOs to thrive.

Historica lly speaking, the term fixedbase operator (FBO) originated in the US and dates back to 1926. During the years following World War I, aviation had caught the popular fancy and many adventurous pilots moved around the country, entertaining appreciative crowds with barnstorming stunts. The US Air Commerce Act of 1926 served to distinguish between mobile support teams that travelled along with the show aircraft from one venue to another, and the more structured type of service provider firmly entrenched in one place (and thus the term fixed based operator). Perhaps there was another need to have a ‘fixed’ support system—the increasing complexity of the nature of the support required. Since then the concept has consolidated in the US into a fairly well defined and understood one. The Federal Aviation Authority defines it as “A commercial business granted the right by the airport sponsor to operate on an airport and provide aeronautical services such as fuelling, hangarage, tie-down and parking, aircraft rental, aircraft maintenance, flight instruction, etc.” As is evident from the above, the concept is predicated to continually mobile operations wherein aircraft from an operator frequently move out from their base for operations—thus requiring support from the station they move to. Scheduled airlines would have their own support systems at all the stations they operate to and thus the FBO concept is applicable to general aviation aircraft only. The US currently has 5,245 listed FBOs for the 20,000 airports across the nation.

In contrast to the defined version of the FBO in the US, in India, the understanding on the term is a bit obfuscated. Under the tab “operators” in the Directorate General of Civil Aviation (DGCA) site, the term does not find a place while in usage it conveys different things to different groups. Loosely speaking, any service provider or vendor offering one or more services or products e.g. refuelling, ground handling, passenger and/or cargo handling, engineering support, flight clearances, customs and immigration facilitation, lounge facility, transportation and so on at an airport is referred to as an FBO. This is in contrast to the ‘omnibus’ concept of FBO wherein one single operator provides all support to a visiting or transiting aircraft. So, is there a need for FBOs in India?

The simple, one word answer to that question is “yes”. However, there is a need to qualify that affirmative with some explanations. In June 2010, Shaurya Aviation Private Limited (SAPL) was designated as the FBO for Delhi airport; there was immediate apprehension amongst the general aviation operators that a full scale FBO model (maintenance, ground handling, passenger handling, etc) would be thrust down their throats by SAPL. This did not come up due to strong resistance from the general aviation operators but the dispensation that did result from the SAPL designation was also not a very happy situation for them. The reason was that as SAPL now had a monopoly over the general aviation facility; no general aviation departure could take place without having to transit through the general aviation lounge, and the rates for the handling and nominal usage of facilities were prohibitive. After some downward movement in the rates originally announced, general aviation operators unwillingly accepted the regime. Since then similar facilities have come up in other stations with the notable one being in Mumbai. At no station, however, is the general operator community satisfied with the high costs especially because some of the services provided by FBOs are not essentially the needed ones.

Do the general aviation operators in India need FBOs? Most operators would respond in the negative. The reason for this unpopularity of the FBO concept in India is the fact that it is not in response to the demands of the aircraft operators that these FBOs have come up but as a result of airport operators’ predatory disposition. The ostensible reason given by airport operators is security concerns but this argument is defeated by the fact that wherever general aviation operators are stopped from carrying out self-handling, the manpower released by them as redundant is promptly recruited by the monopolistic FBO. Most general aviation operators feel that the thrusting of a single FBO down their unwilling throats at exorbitant rates runs contrary to not only the spirit of Competition Act 2002 (which replaced the Monopolies and Restrictive Trade Practices Act 1969 in 2009) but also in letter. The Airport Economic Regulatory Authority (AERA) Act of 2008 and the consequent establishment of an authority (AERA) for the purpose of regulating economic activities at airports is an inadequate act—limited in scope and applicability. The AERA has so far not proved to be of any help to aircraft operators inasmuchas their plaintive cries about the ground handling policies at metros being monopolistic (or oligopolistic) have gone unheeded.

While the FBO concept is well entrenched in the US and to a lesser extent in Europe, it is in its infancy in Asia—commensurate with the lower levels of Asian general aviation (including private and business aviation). Hong Kong, Macau, Singapore, Kuala Lumpur and Shanghai have some FBOs while India has no service provider actually deserving the title of FBO. Those few companies that do provide services and products at airports offer some piecemeal services; perhaps the only advantage they offer is that they do so on credit basis.