INDIAN ARMED FORCES CHIEFS ON OUR RELENTLESS AND FOCUSED PUBLISHING EFFORTS

The insightful articles, inspiring narrations and analytical perspectives presented by the Editorial Team, establish an alluring connect with the reader. My compliments and best wishes to SP Guide Publications.

"Over the past 60 years, the growth of SP Guide Publications has mirrored the rising stature of Indian Navy. Its well-researched and informative magazines on Defence and Aerospace sector have served to shape an educated opinion of our military personnel, policy makers and the public alike. I wish SP's Publication team continued success, fair winds and following seas in all future endeavour!"

Since, its inception in 1964, SP Guide Publications has consistently demonstrated commitment to high-quality journalism in the aerospace and defence sectors, earning a well-deserved reputation as Asia's largest media house in this domain. I wish SP Guide Publications continued success in its pursuit of excellence.

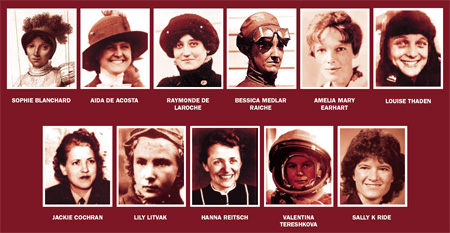

First Ladies

Elizabeth Thible of France was the first woman to leave the surface of the Earth; Jeanne Labrosse the first to fly solo in a balloon; Aida de Acosta the first to pilot a powered airship; Raymonde de Laroche of France the world’s first licensed female pilot—they and several more of their gender form the elite club of women fliers who shattered the glass ceiling in aviation

The first woman to leave the surface of the Earth did so on June 4, 1784. Elizabeth Thible of France was so thrilled floating a mile above the ground in a hot-air balloon that she reportedly burst into song. Later, the Chief of Police of Paris remarked women could not possibly stand the strain of ascending in balloons and that, for their own sake, they should be protected from the temptation to fly. Jeanne Labrosse did not heed this worthy counsel and in 1798 she became the first woman to fly solo in a balloon. A year later she also made the first parachute jump by a woman. In 1809, Sophie Blanchard crashed to her death while flying a balloon—the first female fatality due to aviation. This mishap made a critic declare, “A woman in a balloon is either out of her element or too high in it.”

Aida de Acosta was the first woman to pilot a powered airship. In 1903, in Paris, she needed just three flight lessons in a dirigible before venturing to take it up by herself. Her parents were appalled. Certain that no man would marry a woman who had done such an unbecoming thing they managed to hush it up. The truth only came out three decades later. In 1908, Thérèse Peltier became the first woman passenger in an aeroplane. Then she learned to fly and reportedly made at least one solo flight in Turin, Italy. In March 1910, Raymonde de Laroche of France obtained a licence from the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI) and became the world’s first licensed female pilot.

Some feel that women like to do things differently and Blanche Stuart Scott (the US) proved them right. In September 1910, Blanche was practising solo taxiing in a biplane, prior to taking flying lessons. A limiter fitted on the throttle apparently moved and she opened the throttle more than required, inadvertently getting airborne. The bystanders may have been forgiven for expecting an almighty crash. However, she climbed to an altitude of 40 feet before making a gentle landing. Since her ascent was “accidental” it is not officially regarded as the first flight by an American woman. That honour goes to Bessica Raiche who accomplished the feat a month later. It wasn’t until August 1911 that Harriet Quimby became America’s first licensed female pilot. A decade later, Bessie Coleman overcame barriers of race as well as gender. Refused entry into American flying schools, she eventually earned her pilot’s licence in France, becoming the first African-American (male or female) in the world to do so. Returning to the US, she opened her own flight school in 1921. Unfortunately, she died in a crash five years later.

The early decades of the 20th century exacted a terrible toll on aviation’s pioneers. The machines fondly called aeroplanes were hardly that—such ramshackle and fragile contraptions were they. The scene was also one of complete anarchy. For several years there was little or no regulation—it was not considered necessary. Women took to aviation enthusiastically though they faced great difficulty in being accepted for flight training or joining flying professions. The widely shared sentiment was that women had no place in the sky. Doubts were raised about their ability to control a plane—considering their weaker physique and the thinner air in the upper atmosphere. But the handiest argument was that women were prone to panic and were temperamentally unfit to fly. Meeting with determined resistance and stumbling blocks everywhere, deliberately excluded from piloting passengers, women decided to do their own thing. Many got involved in record-breaking and long-distance flying or dangerous stunts to attract attention and earn money. Daring women pilots flew as high and as fast as the men, often breaking records set by men and defeating them in races. Who can forget Amelia Earhart, founder president of The Ninety-Nines and arguably the most famous female pilot in history? Her solo flight across the Atlantic in 1932 marked a dramatic turning point. At last people began to accept that women could, indeed, fly.