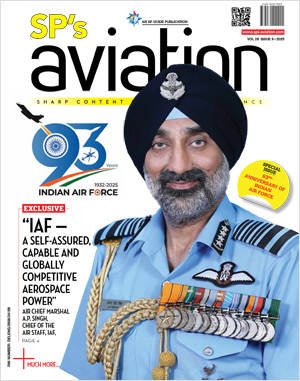

INDIAN ARMED FORCES CHIEFS ON OUR RELENTLESS AND FOCUSED PUBLISHING EFFORTS

The insightful articles, inspiring narrations and analytical perspectives presented by the Editorial Team, establish an alluring connect with the reader. My compliments and best wishes to SP Guide Publications.

"Over the past 60 years, the growth of SP Guide Publications has mirrored the rising stature of Indian Navy. Its well-researched and informative magazines on Defence and Aerospace sector have served to shape an educated opinion of our military personnel, policy makers and the public alike. I wish SP's Publication team continued success, fair winds and following seas in all future endeavour!"

Since, its inception in 1964, SP Guide Publications has consistently demonstrated commitment to high-quality journalism in the aerospace and defence sectors, earning a well-deserved reputation as Asia's largest media house in this domain. I wish SP Guide Publications continued success in its pursuit of excellence.

- A leap in Indian aviation: Prime Minister Modi inaugurates Safran's Global MRO Hub in Hyderabad, Calls It a Milestone

- All about HAMMER Smart Precision Guided Weapon in India — “BEL-Safran Collaboration”

- India, Germany deepen defence ties as High Defence Committee charts ambitious plan

- True strategic autonomy will come only when our code is as indigenous as our hardware: Rajnath Singh

- EXCLUSIVE: Manish Kumar Jha speaks with Air Marshal Ashutosh Dixit, Chief of Integrated Defence Staff (CISC) at Headquarters, Integrated Defence Staff (IDS)

- Experts Speak: G20 Summit: A Sign of Global Fracture

Jean Batten (1909 - 1982)

A glamorous and reclusive woman, Jean Batten was known as the “Greta Garbo of the Skies”. She was one of the finest female aviators of the golden age of aviation, perhaps a more professional pilot than her better-known contemporaries.

Jean Batten, born on September 15, 1909, in New Zealand, studied ballet and music and could have become a gifted concert pianist. However, when just 18, she was inspired by Charles Lindbergh’s epic solo flight across the Atlantic Ocean and her ambitions swung dramatically towards aviation. Her decision was sealed following a joyride with the great Australian aviator Charles Kingsford Smith. Two years later, Jean travelled to England along with her mother with the express purpose of joining the London Aeroplane Club and learning to fly. She made her first solo flight in 1930 and gained her private and commercial licences by 1932.

Jean, however, was not a remarkable pilot, at least to begin with. During an early solo flight, she overshot the runway on landing, hit a wire fence and turned turtle. Fortunately, she emerged unhurt from the wreck. After she acquired her commercial licence, she was determined to fly to Australia and break Amy Johnson’s record of 19.5 days. The first time she tried, in 1933, she made it to Karachi (then part of India) in a Gipsy Moth. But she had to negotiate two severe sandstorms, the engine stopped and she force-landed the plane, wrecking it in the process. A year later, another Gipsy Moth got her only till Rome before she ran out of fuel at night and crash-landed in the dark with great skill. This rang the curtain down on her second attempt. However, she was not done yet. She had the Gipsy Moth repaired, flew it back to London, borrowed the lower wings from another aeroplane, and just two days later, on May 8, 1934, she set out again. This time she made it to Darwin, Australia, in 14 days 22½ hours, shattering Amy Johnson’s time by over four days. It was the age when people were thrilled by each new spectacular aviation achievement and would flock to see their flying heroes. Jean Batten became an instant world celebrity.

Earlier she was dependent on others to finance her aircraft, but now she could buy her own aeroplane for the first time. It was a Percival Gull Six monoplane, which she named Jean. In 1935, she set a world speed record flying from England to Brazil through the South Atlantic in the Percival Gull in 61 hours 15 minutes. She was the first woman to do so and was awarded the Order of the Southern Cross. But New Zealand, her home country, beckoned. In 1936, she established another world record with a solo flight from England to New Zealand. Before flying across the dangerous Timor Sea, she told the base commander: “If I go down in the sea no one must fly out to look for me...I have no wish to imperil the lives of others.” Indeed, she was fearless and sometimes took huge risks in dangerous weather conditions. Her successful long-distance solo flights were brilliant navigational feats, achieved with only a map, a watch and a simple magnetic compass, no radio. The 22,758 kilometres journey from England took 11 days and 45 minutes, a time which was to remain a solo record for 44 years. At her birthplace of Rotorua, New Zealand, she was honoured by the local Maori tribe. She was given a chief’s feather cloak and a Maori title which translates to “Daughter of the Skies”.

But aviation also brought her personal tragedy. In February 1937, she returned to Sydney to meet the man whom she was to marry later that year. However, the day she arrived, he was killed in an air crash. It was not till many months later that she was able to get airborne again. This time she flew the Percival Gull from Australia to England in a spectacular time of five days and eighteen hours. In the process she established a solo record for pilots of either gender, and became the first person to simultaneously hold England-Australia solo records in both directions. Fittingly, in 1938, she became the first woman to be awarded the medal of the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale, the most highly-prized aviation honour. This marked the summit of her aviation achievements.