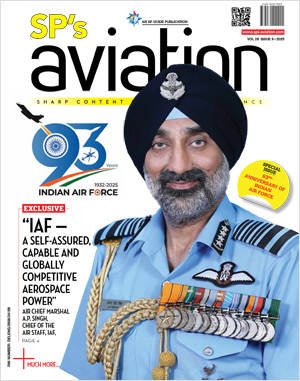

INDIAN ARMED FORCES CHIEFS ON OUR RELENTLESS AND FOCUSED PUBLISHING EFFORTS

The insightful articles, inspiring narrations and analytical perspectives presented by the Editorial Team, establish an alluring connect with the reader. My compliments and best wishes to SP Guide Publications.

"Over the past 60 years, the growth of SP Guide Publications has mirrored the rising stature of Indian Navy. Its well-researched and informative magazines on Defence and Aerospace sector have served to shape an educated opinion of our military personnel, policy makers and the public alike. I wish SP's Publication team continued success, fair winds and following seas in all future endeavour!"

Since, its inception in 1964, SP Guide Publications has consistently demonstrated commitment to high-quality journalism in the aerospace and defence sectors, earning a well-deserved reputation as Asia's largest media house in this domain. I wish SP Guide Publications continued success in its pursuit of excellence.

Women’s Air Derby (1929)

The US had just 70 licensed female pilots who made a living stunt flying, barnstorming, and wingwalking for air shows. Many died young.

A quarter of a century after the dawn of powered flight, aircraft were still flimsy contraptions of balsa wood, fabric and wire. Their engines were fickle affairs, prone to overheat or to quit without warning. In the absence of instruments and navigational aids low flying was the norm—there was no other way to navigate. To follow a road or rail track marked on a motoring map was foolproof (well, almost). If lost, a pilot would put the machine down on a field reasonably bereft of trees and cattle, ask for directions, and take-off again. The United States had just 70 licensed female pilots who made a living stunt flying, barnstorming, and wing-walking for air shows. Many died young. They could do practically anything the men did—set speed and altitude records, test fly, carry out decent mechanical repairs, and parachute from planes. But there was one thing they couldn’t do—race. Cross-country air racing was strictly for men.

All that changed in 1929. The first Women’s Air Derby that began on August 18 was a transcontinental event, and the opening attraction of the US National Air Races. The contest attracted considerable interest, not so much for the $2,500 first prize as for the shortcut to professional fame it afforded participants. The organising committee had been concerned about women flying over the Rocky mountains and helpfully proposed shifting the starting point to Omaha, Nebraska. However, the women would have none of it, so the start was moved back to Santa Monica. Only 40 women met the qualifying requirements: a licence from the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI) and 100 hours of solo flying, including 25 hours of solo cross-country. Eighteen of them plus two Europeans began the race. The women took their mission very seriously, aware of the constant peril. They flew over parched deserts, lush green valleys and the frigid peaks of the Rockies, navigating by dead reckoning and roadmaps. Swirling sandstorms, heavy rain and haze were par for the course. Forced landings were many; the pilots fixed their planes and flew on.

Tragedy struck on day two itself when Marvel Crosson died after she bailed out too low for her parachute to open. The critics of the whole crazy enterprise felt vindicated. “Women Have Conclusively Proven That They Cannot Fly!” and “Race Must Be Stopped”, screamed the headlines. The women, however, were determined to continue. They had support from some of the best known pilots and celebrities of the day. They also had a strong feeling of sisterhood that kept them going—a sense that they were making history together. Besides, glamour compensated for some of the many hardships. Each overnight halt meant receptions and festivities, with the pilots having to change from rough flying gear into party gowns, and suffering some more sleep deprivation, before launching early the next morning. Inevitably, their looks and clothes gained more press coverage than their flying. Humourist Will Rogers, noticing that the pilots couldn’t resist taking out their compacts and doing their faces, said that it looked to him like a “powder puff derby”. There was no malice in his remark and later the women themselves adopted the name for the annual race. The problems they encountered were common rather than gender-specific. Three pilots dropped out when their planes were wrecked beyond repair; one was too ill to continue. Ruth Nichols, who had been in the lead, had perhaps the most heart-breaking experience. While testing her repaired plane on the last morning of the race, she hit a tractor. Although uninjured she was forced to quit. But 15 intrepid women completed the 2,800-mile race to Cleveland, Ohio, in eight days, and a large crowd was on hand to applaud their achievement.