INDIAN ARMED FORCES CHIEFS ON OUR RELENTLESS AND FOCUSED PUBLISHING EFFORTS

The insightful articles, inspiring narrations and analytical perspectives presented by the Editorial Team, establish an alluring connect with the reader. My compliments and best wishes to SP Guide Publications.

"Over the past 60 years, the growth of SP Guide Publications has mirrored the rising stature of Indian Navy. Its well-researched and informative magazines on Defence and Aerospace sector have served to shape an educated opinion of our military personnel, policy makers and the public alike. I wish SP's Publication team continued success, fair winds and following seas in all future endeavour!"

Since, its inception in 1964, SP Guide Publications has consistently demonstrated commitment to high-quality journalism in the aerospace and defence sectors, earning a well-deserved reputation as Asia's largest media house in this domain. I wish SP Guide Publications continued success in its pursuit of excellence.

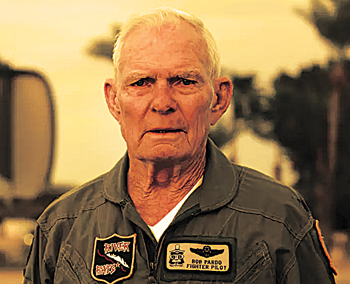

Bob Pardo (1934-2023)

In 1989, the USAF reviewed the legendary “Pardo’s Push” incident. It belatedly recognised that Bob Pardo had displayed exemplary leadership, airmanship and courage, not to mention creative thinking on that fateful day.

Military aviation is replete with stories of men and women who showed amazing heroism in combat. Bob Pardo was one such aviator who, in just 20 minutes in hostile skies, earned a place in the sun.

John Robert Pardo was born on March 10, 1934, in Lacy Lakeview, Texas. Two years after graduating from high school he joined the United States Air Force (USAF). He served combat tours during the Vietnam War in 1966 and 1967. In the course of 132 missions he was awarded the Purple Heart, the Distinguished Flying Cross and the Silver Star.

On March 10, 1967 – his 33rd birthday – Captain Pardo and his weapon system officer, Lieutenant Steve Wayne were flying an F-4 Phantom II. Their target was the only steel production complex in North Vietnam, near Hanoi. Accompanying them in another F-4 were Captain Earl Aman and Lieutenant Bob Houghton. The Hanoi area was one of the most heavily defended in the history of aerial warfare, with perhaps half a dozen surface-to-air missile sites and more than 1,000 antiaircraft guns. Many US aircraft had been shot down in missions against this elusive target. After several frustrating days when the target had been obscured by low clouds, the sky was clear. During the attack, both jets were hit by ground fire. Aman’s plane was badly damaged and fuel began gushing out of a ruptured fuel tank. He realised that he would not have enough fuel to rendezvous with a USAF KC-135 tanker aircraft patrolling over Laos, and hence started climbing prior to ejecting. Ejection over Vietnam meant certain capture with the prospect of being promptly killed or being ill-treated in a prison camp.

Pardo’s aircraft seemed only moderately damaged and he could have reached the KC-135 and refuelled before recovering safely at base. However, as he said later, “How can you fly off and leave someone you just fought a battle with? The thought never occurred to me.” Soon Aman’s jet flamed out and began descending at around 3,000 feet/min. In desperation, Pardo decided to push the stricken aircraft into Laos. This sight is not uncommon on India’s roads where a two- or three-wheeler pushes or tows another similar vehicle that has run out of petrol. But this was something else altogether – a military fighter weighing around 15 tonnes and gliding at 250 knots.

Pardo first tried prodding the damaged plane using Aman’s drag chute compartment but turbulence interfered. Then he hit upon a brilliant idea. He radioed Aman to lower his tailhook. The heavy-duty tailhook was fitted to enable Naval F-4 pilots to bring the aircraft to a quick stop during a carrier deck landing. Pardo gently manoeuvred his aircraft under Aman’s, till Aman’s tailhook rested against a bit of metal near Pardo’s cockpit canopy. It worked, and Aman’s rate of descent soon reduced to 1,500 feet/min. However every 15-30 seconds Aman’s tailhook would slip off Pardo’s jet. Pardo would then back off a little before cautiously closing in again. If he had been slightly careless or impatient the tailhook would have pierced his canopy glass.

Even as he struggled to assist his comrade, Pardo’s aircraft started showing signs of distress. A warning light flashed, indicating that his left engine might be on fire, so it had to be shut down. Pardo tried restarting it, but the temperature gauge went off the clock so he turned it off permanently. In effect, the two jets were now flying under the power of just one out of four engines.

However, although Pardo’s aircraft was running out of fuel, he had pushed Aman’s jet around 140 km. More importantly, the planes had reached Laotian airspace. There the four aircrew ejected safely at an altitude of 1,800 m. Pursued by some none-too-friendly Laotian villagers they managed to evade capture and were finally rescued by US helicopters. Back at their base in Thailand, Pardo faced the ire of a USAF hierarchy ultrasensitive about combat losses. He was nearly court-martialled for not saving his own aircraft, but was finally let off with a reprimand. Pardo had no regrets saying, “(We) lost eight airplanes that day, but the four of us were the only ones that made it back.”

In 1989, the USAF reviewed the legendary “Pardo’s Push” incident. It belatedly recognised that Bob Pardo had displayed exemplary leadership, airmanship and courage, not to mention creative thinking on that fateful day. Both he and Wayne received Silver Stars for their heroism in saving their imperilled comrades.

Pardo’s loyalty to Aman didn’t end there. When he learned that Aman was suffering from Lou Gehrig’s disease and had lost his voice and mobility, he created the Earl Aman Foundation which funded a voice synthesiser, a motorised wheelchair, and a computer for Aman. Bob Pardo died on December 5, 2023, in Texas. He was 89.